Astronomers analyzed the latest data returned by the Webb Space Telescope and found unexpected surprises.

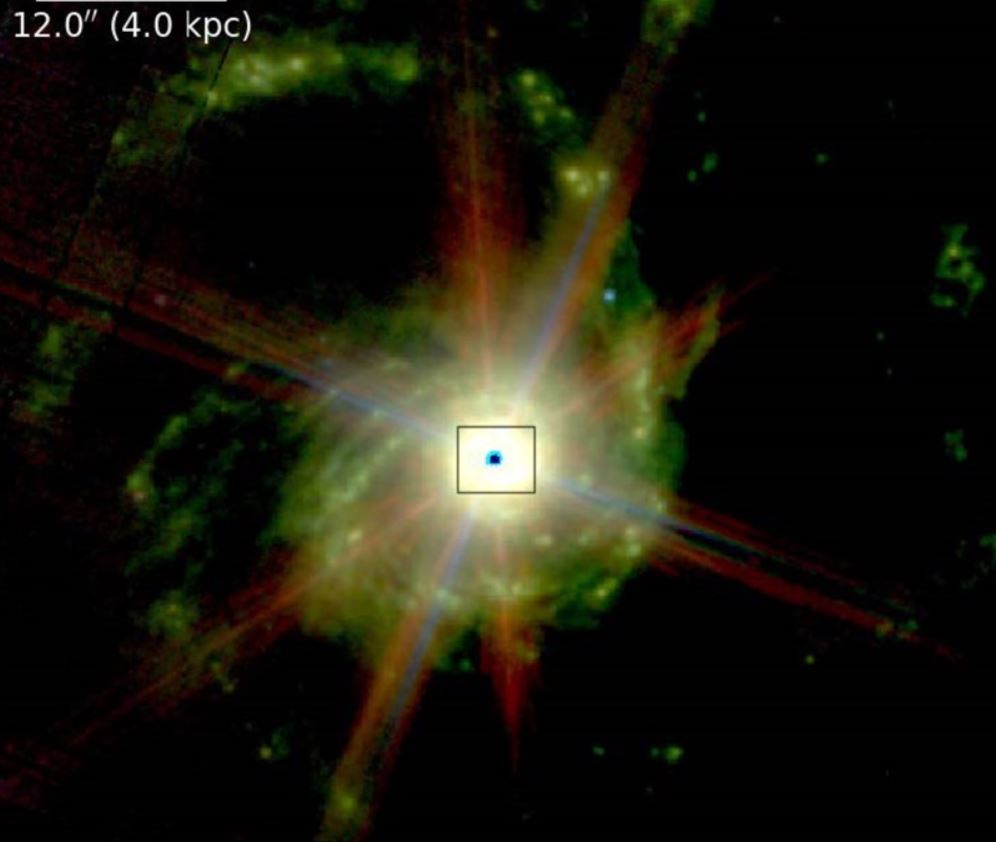

Organic molecules originally thought to be destroyed by the intense high-energy radiation around the black hole at the center of the galaxy are still visible under the mid-infrared camera of the Webb Space Telescope.

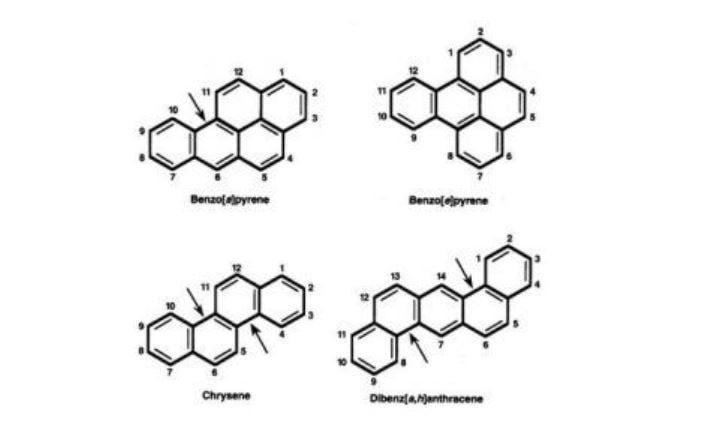

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH or PAHs for short) are hydrocarbons with a cyclic structure, with more than 100 chemical structural formulas.

In nature, it often occurs in coal and tar deposits, and incomplete combustion of organic matter is often seen. Many PAHs are confirmed as carcinogens.

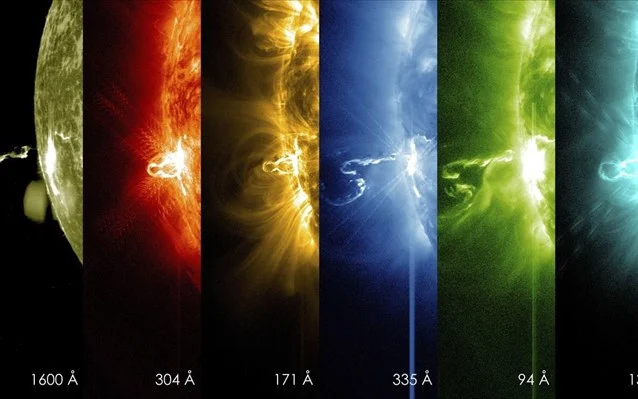

However, in astronomy, interstellar PAH molecules are affected by the radiation of young stars, and emit specific wavelength spectral lines in multiple infrared bands. They are often used by astronomers to track galaxy star formation activities, or star formation rates near active galactic nuclei (AGN).

However, astronomers still have limited understanding of how PAH molecules are affected by radiation. Previous studies predicted that PAH molecules near the center of active galaxies would be destroyed by strong radiation from black holes.

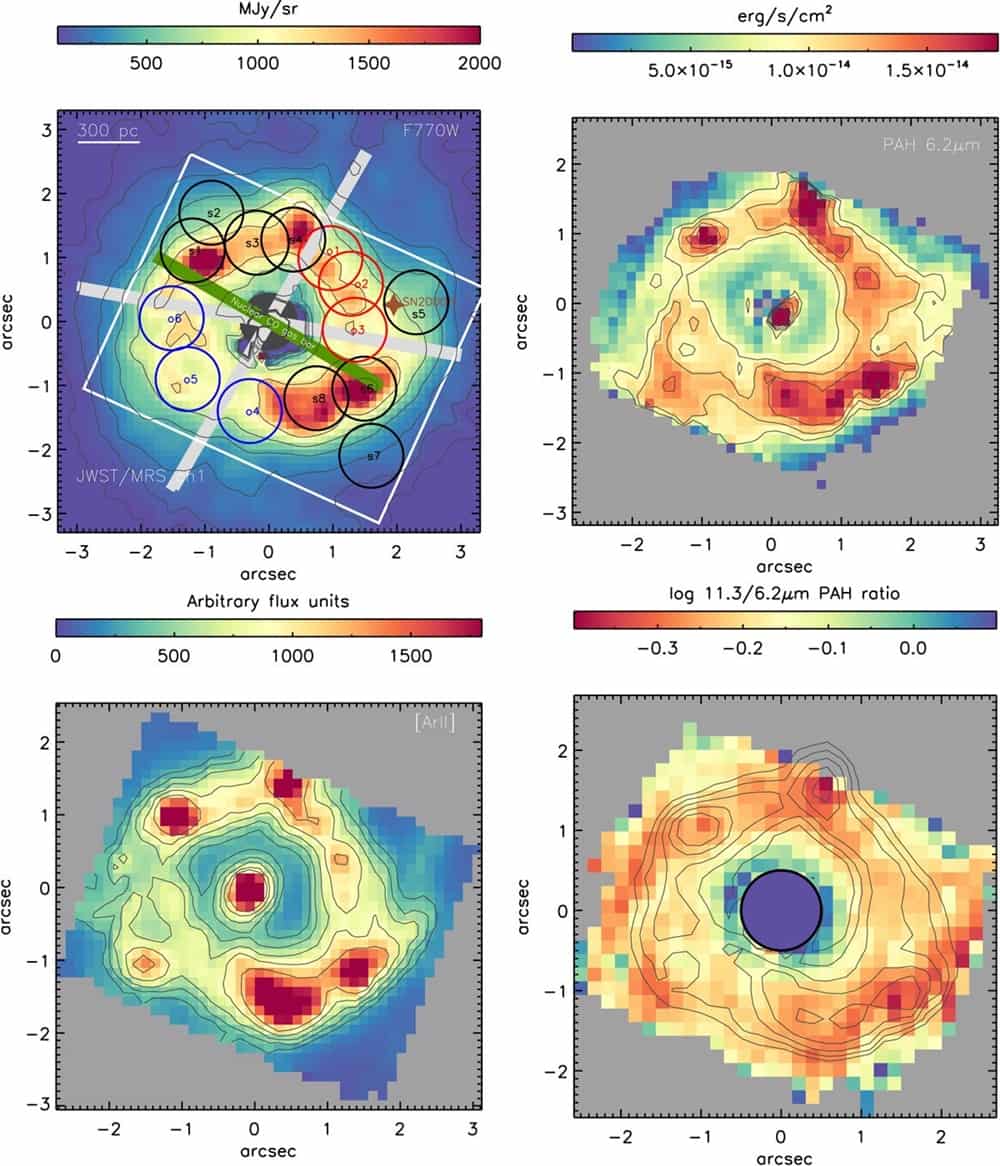

But Oxford University astronomer Ismael García-Bernete and his team used the Webb Space Telescope’s Mid-Infrared Camera (MIRI) to observe the core regions of three galaxies NGC 6552, NGC 7469 and NGC 7319 and found that these organic molecules can survive in extremely harsh conditions.

Even if these PAH molecules survive, the observations still show that the supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy has a significant effect on the molecular properties.

The astronomers found that neutral and large PAH molecules survived in greater proportions, and that the weaker, smaller charged PAH molecules appeared to be more easily destroyed.

Thanks to the ultra-high resolution of the Webb Space Telescope, astronomers were able to observe, for the first time, how PAH molecules survive and their specific properties in the core region of galaxies.

This knowledge could help improve PAH’s models that describe the amount of star formation in galaxies and further help us understand how galaxies evolve over time. The detailed results were published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics (A&A).