Due to the upper limit of the speed of light, the distant galaxies we see now are not what they are today, but the state of billions of years ago, and it is even more challenging to observe the dark matter that does not emit light in distant galaxies.

Recently, scientists observed the oldest dark matter to date, as far as 12 billion light-years away, shedding light on the mysteries of the early universe; the team also found that some regions have less dark matter than theoretical predictions, which will help improve models.

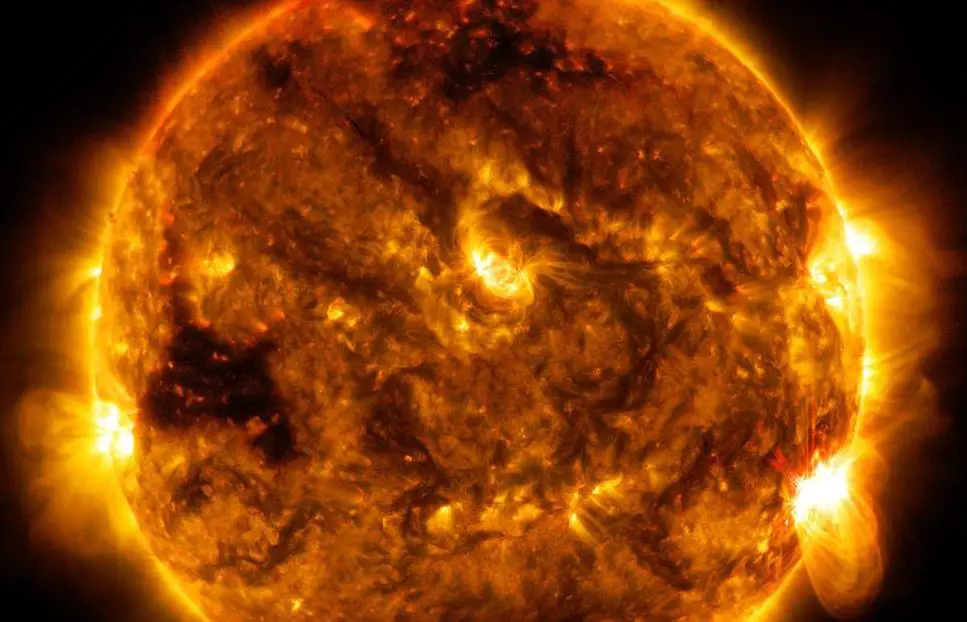

Including the Milky Way, all galaxies in the universe are rotating at an astonishing speed. Physical objects in galaxies should be thrown out by centrifugal force. Obviously, these accidents did not happen. Both the earth and the sun are firmly anchored.

So physicists speculate that there is something invisible filling the galaxies, protecting them from falling apart.

Dark matter is invisible, unfeelable and so far no direct evidence has been found . Although current instruments and equipment cannot directly detect dark matter, we have many methods to confirm the influence of dark matter on the operation of the universe, such as analyzing how dark matter gathers galaxies in Together.

Using this principle, a team from Nagoya University in Japan announced an extraordinary new discovery of dark matter: dark matter halos around many ancient galaxies were found in a deep space region.

It can be traced back to 12 billion years ago, which is equivalent to less than 2 billion years after the Big Bang. It may become the earliest dark matter ring studied by human beings, opening a new chapter in early cosmology.

The team first used data from the Pleiades Telescope to identify 1.5 million gravitationally lensed galaxies, and then combined with microwave background radiation data from the Planck satellite to measure whether these galaxies had dark matter around them and how they distorted microwaves farther away.

Finally, a complete galaxy evolution map is obtained, including the dark matter in and around the galaxy.

One of the most exciting findings from this study has to do with clumps of dark matter.

According to the ΛCDM model, the standard theory of cosmology, the subtle fluctuations in the thin background radiation will attract the surrounding matter to densely accumulate through gravity, forming uneven clumps.

Further stars and galaxies are formed, and the new findings show that the clump measurements are lower than predicted by the ΛCDM model, suggesting that we need to revisit some of the model’s assumptions.

The team reviewed only one-third of the data from the Pleiades Telescope, and the researchers next plan to analyze the full data set, which is expected to be able to more accurately measure the distribution of dark matter in the early universe.

When the Vera Rubin Observatory is put into operation in the future, scientists will have the opportunity to “see” the distribution of dark matter 13 billion years ago.

The new paper is also published in Physical Review Letters.